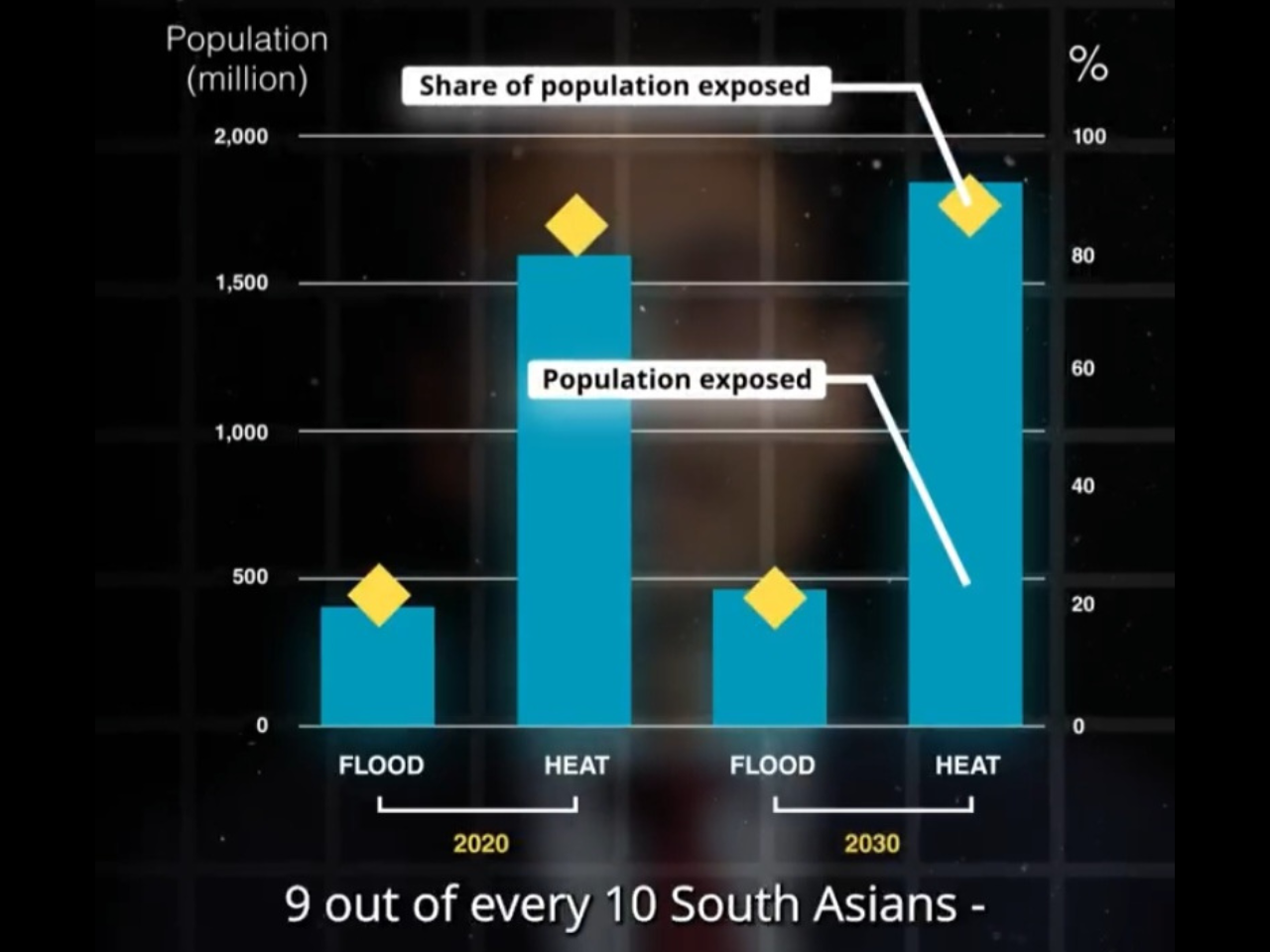

South Asia's Climate Crisis: 90% Population at Risk of Extreme Heat by 2030

Consider using public-private alliances, fiscal tools, and climate risk-informed budgets to enhance adaptive capacity.

The South Asian world is experiencing an increasing vulnerability to extreme temperatures, flooding, and cyclones; therefore, climate adaptation is a pressing development agenda. The area is already the most vulnerable to climate change among emerging and developing markets, and it is estimated that almost 90 percent of its population will be in danger of extreme heat by the year 2030. The exposure in urban context is also observed to be quite alarming: by 2030, 1.2 billion of the urban population (92 percent) is projected to be exposed to extreme heat, and 322 million (24 percent) will face flood risks. An increase in temperature is also lowering labor productivity as the number of hours spent under the sun is becoming unsafe, and their projected losses in heat-related working hours are the most in the world by 2030.

Accepting these weather patterns that are life-threatening requires a holistic approach that incorporates individual initiative and facilitates government policy. Though 80 percent of households and 63 percent of firms are reported to have taken adaptive measures, the majority of the responses are low-cost and basic in nature because of financial and information limitations. Governments can enhance resilience through enhanced access to credible weather forecasts and early warning systems, which have proved useful in mitigating damage in the prone areas. City planning should be done systematically, pushing people out of risky flood areas and emphasizing on construction of resilient infrastructure like drainage, transport, and water systems. Informality and high urban poverty also presuppose the necessity of specific social protection.

As much as it covers 77 percent of the population, the programs should be better-funded, targeted, and scaled within a short period to respond to shocks. Loss incomes may be reduced using shock-responsive cash transfers and diversification of livelihoods, and this would promote long-run adaptation. To conclude, the future of South Asia in risk management to resilience is through the establishment of greater institutions, correcting market failures, investing in resilient infrastructure, and protecting its most vulnerable population from mounting climate extremes.

Latest News

EU's HOUS Committee Takes Bold Steps to Address Housing Crisis by 2026

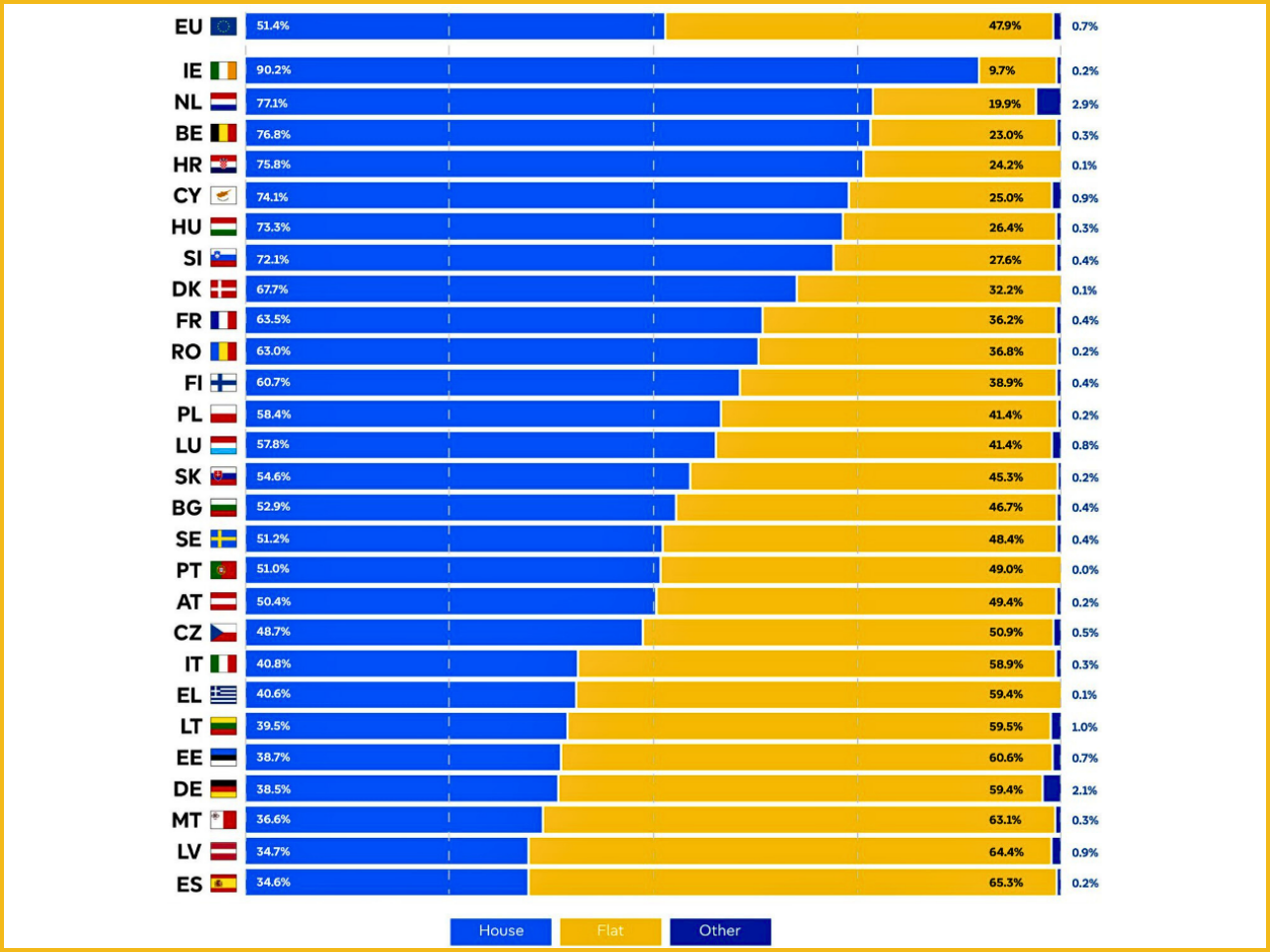

The European Parliament’s HOUS Committee (Housing Crisis in the EU) has a mandate to develop solutions for housing issues in the EU (affordable, sustainable, and decent) aimed at resolving these issues by 2026. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and Eurostat for meetings held in January 2026. These meetings have been very valuable in providing the members of the committee with an improved understanding of housing data and housing policy.

Data Centre Boom Sparks Energy Crisis: Power Companies Scramble to Meet Surging Demand

The industry that capital outlay on data centres may approach approximately 7 trillion dollars by 2030, of which approximately 1.3 trillion dollars will be used in power generation, cooling equipment, and electrical equipment. In Ireland, data centres already represent approximately 20 percent of national electricity consumption, as the example of the digital infrastructure redefining energy demand shapes up that speedily.

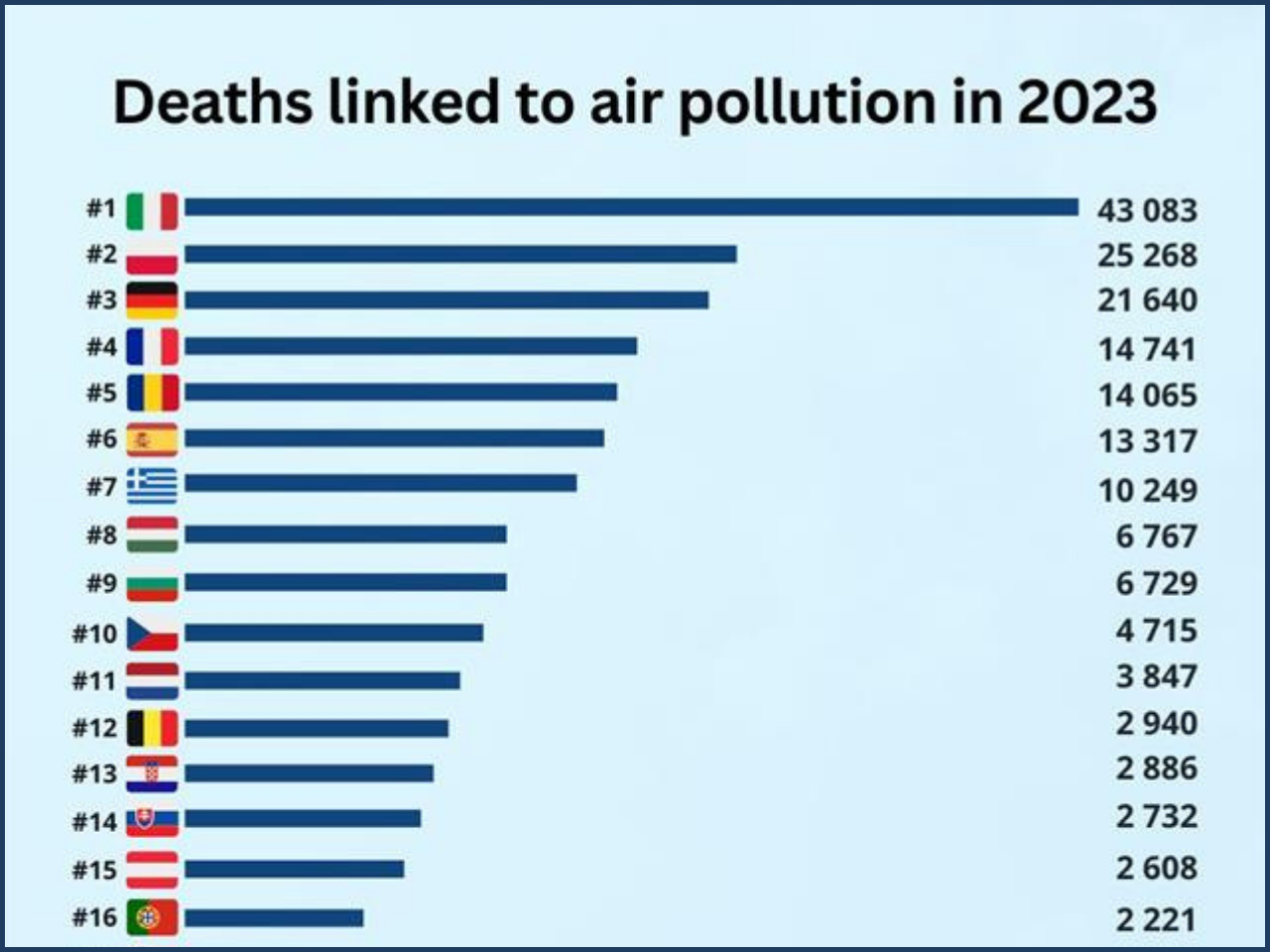

EU's Zero Pollution Action Plan: Aiming for a Toxic-Free Environment by 2050

The European Union’s “Zero Pollution Action Plan” will strive to achieve an environment without toxins by decreasing air, water, and soil pollution to levels that have no effect on human health or the ecosystems’ ability to function properly and provide vital services (e.g., storing carbon or filtering pollution). The plan includes significant targets for progress toward 2030, including a 55% decrease in premature deaths caused by air pollution.

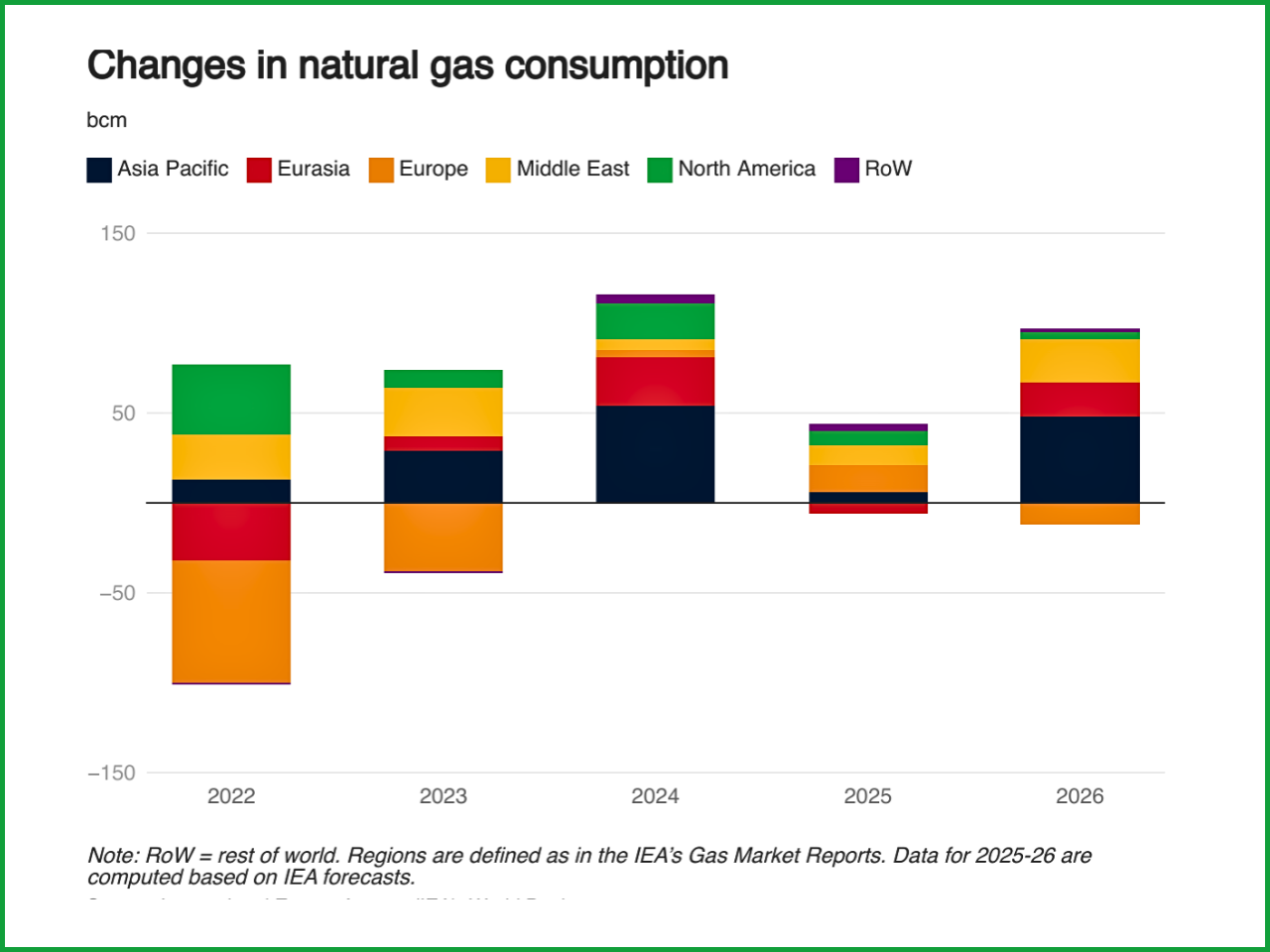

Global Gas Market in Flux: Prices Diverging as LNG Trade Shifts

The World Bank’s gas price index went up slightly, but the trend in prices looks very different depending on where you live. In the United States, natural gas prices kicked up above $5/mmbtu for the first time in three years due to cold temperatures and, on top of other things, increased LNG shipping over to Europe. Throughout Europe, prices for natural gas fell again this week, reaching an all-time low since early 2024 based on declining demand and increasing volumes of LNG imports.

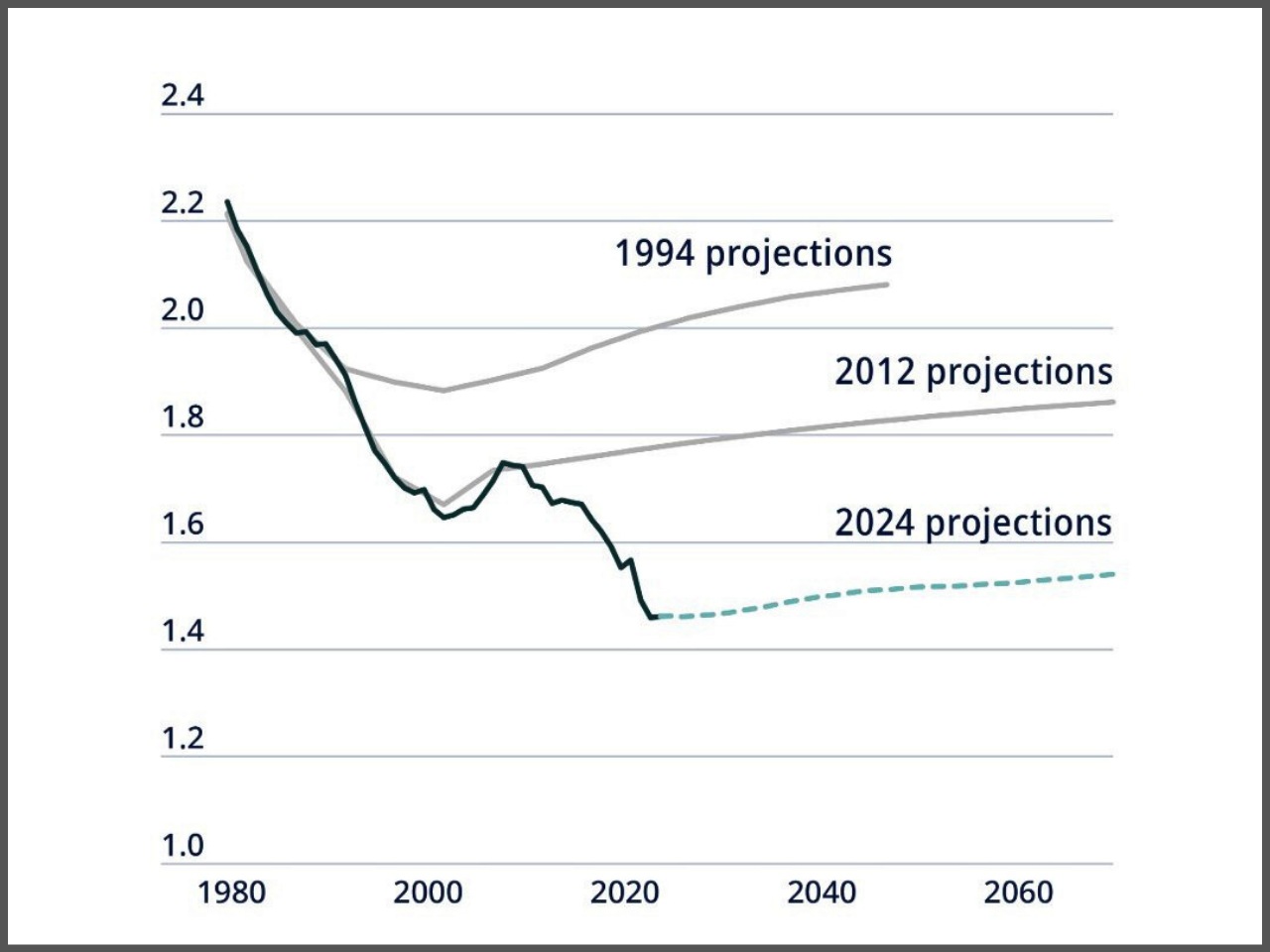

Pension Systems in Crisis: OECD Report Reveals Challenges and Opportunities for Reform

Pension payments offered to future workers are estimated to be about 63% of net wage earnings on average across the world, but there are significant variations between different countries. Women continue to receive monthly pension payments that are roughly 25% lower than the amounts received by men. Imbalances in employment availability for jobs, hours worked per week, or base salary are major contributors to the lifecycle earnings differentials that create the overall pension gap.

Monthly Edition